Here we interveiw Jim Arvanitis. He is widely known as pankration’s “Renaissance Man”, has won numerous Hall of Fame awards in martial arts, including Grandmaster of the Year, Black Belt magazine’s Instructor of the Year, and Panhellenic Athlete of the Decade. The Greek/American has dedicated his life to reconstructing pankration, the ancient combat sport of his Spartan forefathers. By combining evidence from archaeological remains, ancient literary accounts, and his own expansive knowledge of martial arts, Arvanitis has spearheaded pankration’s revival and earned the title “Father of Modern Pankration.”

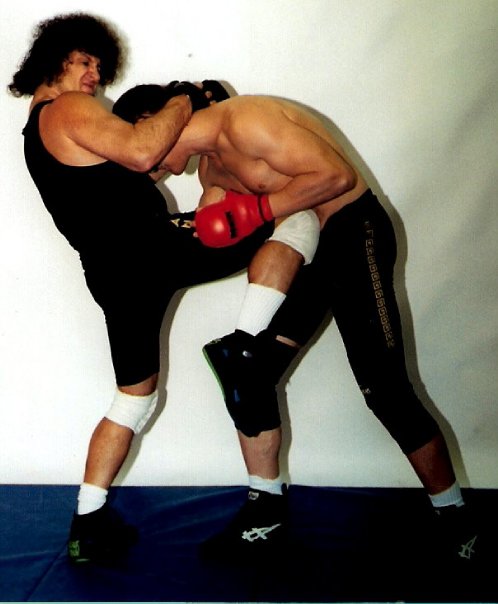

In his formative years, Arvanitis trained in boxing, wrestling, muay thai, karate, and kosen judo. Throughout his training, he adopted a functional approach to martial arts by assimilating or discarding techniques based on combat effectiveness. Arvanitis always emphasized physical fitness and set several world records through feats of strength. To ensure the applicability of his style in modern altercations, Arvanitis became an experienced competitor and street-fighter. His practical approach to hand to hand fighting, including grappling and striking in equal measures, lead Black Belt magazine to name Arvanitis “the first mixed martial artist.”

While continuing his own personal training and experimentation in martial arts, Arvanitis also began disseminating his teachings to the public, including seminars for professional bodyguards, law enforcement personnel, military special forces, and Army Rangers. Arvanitis has made available numerous well-reviewed books and videos on pankration and martial arts. Following his recent publication, Pankration: The Unchain Combat Sport of Ancient Greece, Arvanitis will be publishing two more books in the upcoming year and featuring in his third cover article for Black Belt magazine.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

- New Reseach

- Training and Preperation

- Modern Martial Artists

- Ancient Pankration

- Comparing Modern and Ancient

- Applying Techniques to Combat

New Reseach

Your new book “Pankration: the Unchain Combat Sport of Ancient Greece” heavily emphasizes the biomechanics of fighting. Are there any techniques or concepts in your newest publication that you previously believed in, but now reject in light of your continued research into martial arts?

JIM ARVANITIS: I see my martial arts journey as a process of constant learning. In that sense, I still practice those techniques which I feel are FUNCTIONAL either standing or on the ground. For me, a true pankratiast must be adaptable to any situation, and be proficient at skills that enable him to survive in any means of physical engagement … ring, cage, street, or wherever it happens to take place. So I remain confident in that which I have accumulated through the years though I am free to modify where necessary for optimum efficiency. That is the beauty of a non-stylized mindset … there is no definitive set of maneuvers that must remain stagnant and unchanged due to the confining shackles imposed by tradition.

Have modern understandings in nutrition and kinesiology advanced your reconstruction of certain techniques beyond the level of ancient pankration? Does this hold true for MMA fighters?

JIM ARVANITIS: I agree with the quote, “There is nothing as constant as change.” With advancements in technology there is always the need to stay current for self-improvement and growth. Ancient pankration is merely a blueprint in my evolution of “all-powers” combat. Its training methodology, diet, and techniques were appropriate for a different time. More essential was that I continually educate myself from various contemporary sources to understand what could make me a better martial artist and athlete. This is the value of cross-training and independent research. MMA coaches are following this same approach for adequately preparing their fighters for competition. They involve specialists in striking, wrestling and BJJ, nutrition, strength and conditioning, and strategic planning for this purpose in their training camps.

Training and Preperation

What convinced you to add weight lifting to your calisthenics and isometric exercises in honing your body for combat?

JIM ARVANITIS: Due to my relatively small frame as a teenager, I felt that incorporating weight training into my workout routine would aid in making me stronger. My later study in the college of kinesiology and sports exercise gave me a better comprehension of the human body and those muscle groups that were applicable in combat movements. This was vital for striking effectiveness, and very instrumental in the grappling (pale) and ground (kato) phase.

You have endorsed both researching your opponent before a fight and remaining adaptable to change. What kind of training schedule, as far as intensity, activates, or exercises, do feel are most effective for modern MMA fighters the week before a competition?

JIM ARVANITIS: I might suggest light contact sparring, combat simulation drills with equipment, and analyzing films of an opponent in action to exploit particular strengths and weaknesses. Too much hard sparring so close to a scheduled bout should be avoided. Going into a fight injured from training or having to withdraw altogether are not good options. The MMA competitor should stick to the fight plan devised by his coaches. Deviation from this plan might work against him, but he must always remain open and pliable enough to take advantage of mistakes made by the opposing fighter during the course of a match.

MOVEMENT AND RHYTHM

The ‘movement’ concept endorsed by people like Ido Portal, which revolves around training fluid and complex movement patterns seen in gymnastics and breakdancing, is gaining traction with MMA fighters. What are your thoughts on training in other disciplines outside of martial arts to improve body movement?

JIM ARVANITIS: I have always emphasized fluidity of motion in combat from the outset. Training in gymnastics and certain forms of dance can certainly improve one’s unpredictability in combat due to swift, agile footwork and upper body movement. From my study of boxing, I found that boxers that bob and weave and slip punches effectively were much more difficult to hit squarely or knock out. Elusive mobility is a core principle of my personal fighting philosophy.

Elusive mobility is a core principle of my personal fighting philosophy

The Greeks incorporated the pyrrhic dance to help develop rhythm in combat, are there similar exercises you incorporate?

JIM ARVANITIS: Similar to the pyrrhic dances, I believe in implementing music (including rock as well as that of modern-day Greece) in many aspects of my training. For instance, I listen to my favorite songs while I jump rope, run, and when hitting equipment. I also shadow fight where I focus on developing my footwork and music plays an important role to promote my sense of rhythm. The ancients performed their combative maneuvers to the accompaniment of musical instruments, such as the lyre, to help them in this regard. However, they were free-form practices rather than the memorized patterns of karate’s kata.

Modern Martial Artists

Are there any current Mixed Martial Artists that have caught your attention and why?

JIM ARVANITIS: There are several outstanding mixed martial artists currently competing. I like those who bring the true spirit of respect and honor into the cage as opposed to ridiculous WWE antics. I also notice those who are well-conditioned with excellent cardio. In my humble opinion, being fit is at least 50% of the fight game. The Diaz brothers are good examples of MMA fighters who just keep going and going. They do a lot of running and triathlons which I also have participated in for several years. I feel activities like these help with maintaining proper energy levels. Many excel as either standup strikers or grapplers but there are but a handful that are truly well-rounded. Even this Mcgregor fellow who receives so much PR for the UFC needs to improve his skill-set on the ground, especially if he draws a tough grappler such as Khabib Nurmagomedov. On the other side of the coin, fighting is never an exact science … sometimes all it takes is a fluke punch or a flash injury to end a contest.

Bruce Lee’s open-minded approach to martial arts, like your own, predated many concepts in MMA. Have you had any interactions or conversations with Bruce Lee, or been influenced by his work?

JIM ARVANITIS: When I first arrived in Los Angeles in 1973 to shoot the landmark cover story for Black Belt magazine, the editor wanted to arrange a meeting with Bruce Lee. He felt the similarities in thinking would make for an interesting discussion. Lee, however, was filming in Hong Kong at the time. Unfortunately, he died a few days later. While I respect Lee’s legacy, I was never actually influenced by his work. Many tend to compare my concepts with his, but the fact is that our backgrounds are entirely different. Bruce emerged primarily from a classical wing chun background and branched out later in his ideology, whereas I came from Western combat sports where freedom of expression and movement were already ingrained in my cognitive and physiological makeup. I evolved my own personal art exclusively from my individual studies and experiences. I really had no preference as to striking or wrestling … I was equally passionate about both. I also feel that grappling and ground-based skills were far more evident in what I was doing than Lee’s original JKD. One thing we did have in common is our passion for martial arts and being fit, and there’s no denying that!

Ancient Pankration

In reconstructing pankration techniques, images recovered from the archaeological record form an important source of information. The medium cannot, however, easily convey combination or sequence based attacks. How did you address this issue?

JIM ARVANITIS: The remnants left to us by the ancient Greeks conveyed to me that the pankratiasts of antiquity embraced totality. They combined boxing, wrestling, and kicking techniques in their Panhellenic festivals as a means of testing their skill, knowledge, and courage in an almost unrestricted mode of combat, both physically and mentally. These images from sculptures and vases, along with literature from poets and philosophers, provided a guide in refining a means of total fighting freedom that was contrary to the more popular martial arts during the early-1970s. Back then, a martial artist was either a standup fighter or grappler. Few were blending both. The combinations and what I call transitions were the direct result of my training in fighting systems that were compatible … boxing, wrestling, catch, kosen judo, muay-Thai, and savate. One of my foremost objectives was to cohesively integrate moves from these so they flowed congruently and worked under the most extreme conditions.

Individuals in Pankration would have developed their own approach to combat based on their physical and physiological characteristics. Do you believe distinct styles/schools of pankration eventually emerged in ancient Greece as a result?

JIM ARVANITIS: While there were no specific “styles” per-se of pankration with their own distinctive names (as in classical karate or kung-fu), ancient Greek pankratiasts were highly influenced by their regions and their athletic trainers. The Elean Greeks, for instance, were extraordinary grapplers and feared for their ability to quickly seize control of their adversaries and submit them with lethal chokes. Before the Spartans discontinued competing in Olympic pankration, they were known for their dominant boxing prowess.

ancient Greek pankratiasts were highly influenced by their regions and their athletic trainers.

The ancient Greeks heavily debated the usefulness of combat sports like pankration in preparing individuals for military action. For instance, Euripides and Plato had reservations but Plutarch and Philostratus stressed its benefits. Why do you believe there wasn’t a widespread consensus? Do you lean towards one side or the other?

JIM ARVANITIS: There will always be critics who question whether a combat sport produces an exceptional warrior in life-or-death conflict. Greek history tells us that on at least one occasion a trained pankratiast (Dioxxipus) defeated an armed and armored hoplite (Coragus) with relative ease. We also have evidence that some highly-regarded combat athletes lost their lives in panoply facing sword and spear. Critics such as Plato (among scores of others) felt that as the sport evolved the greater reliance on ground fighting made pankration useless for war. I believe that while the two share some common characteristics, they’re also vastly different. Being a great military warrior does not make for a great combat athlete. Nor does a great combat athlete make for a great military warrior. Qualifying as both is somewhat of a rarity.

Comparing Modern and Ancient

You mentioned Pankration almost exclusively relied on front kicks, an assertion supported by the archaeological record, because they optimized economy of movement, afforded more balance, and were more difficult to guard against. Do you believe MMA fighters will eventually follow suit?

JIM ARVANITIS: One of my favorite sayings is that “there is nothing new under the sun.” Front kicks have a long tradition in Greek pankration and in its earlier predecessor of pammachon (Gr. total fight). I favor front kicks due to their motion economy, better balance, and their directness makes them more difficult to defend against. The ancient Greeks were realists and minimized unnecessary movement in their techniques. This was due to the impact of battlefield combat on the earliest version of pankration. It was only when it evolved in the Olympic Games did the skills become more diverse, especially in the grappling and ground component. However, I also utilize other kicks to add greater utility to my striking arsenal. We have already seen the effectiveness of the front kick in MMA by some fighters who completely took their opponents out of their game plan by surprising them with this relatively uncommon technique.

Ancient sources consistently mention the advantages of superior size and strength convey to participants in pankration competitions. Do you believe that actively attempting to increase muscle mass and overall bulk is as important as honing timing and precision?

JIM ARVANITIS: Ancient pankration had no weight divisions and most accounts mention that the sport was the domain of the larger, heavier athletes. When training with weights, the goal should be to enhance both speed and strength, not merely size or bulk. Fighters are not bodybuilders. This requires a working knowledge of those exercises that hone these attributes, not hinder them. At the same time, drills for timing and precision are an absolute must in one’s training program. Too much size/bulk can often slow down one’s movements and impede flexibility. A ripped physique from training and diet is visually impressive but does not ensure invincibility in fighting. In addition, size can often be overcome by superior speed and technique.

At the same time, drills for timing and precision are an absolute must in one’s training program

Applying Techniques to Combat

Pammachon, the battlefield origin of the combat sport pankration, was developed with the restrictive hoplite panoply in mind. Because of the different contexts in which they were used, hand to hand combat in pankration and pammachon eventually became distinct disciplines. In a similar manner, when working with armed forces have you altered certain techniques to accommodate for gear and body armor?

JIM ARVANITIS: I teach material based on the needs of my students, and modify techniques and tactical applications accordingly. Pammachon was evident in the earliest pankration events with the limited number of techniques and emphasis on standup (ano) combat, but transforming a pure combat method into a competitive sport is always a complicated task. There were certain elements that worked in the skamma (Gr. sandpit) that would prove futile on the blood-soaked battlefields, and vice versa. The same holds true today when comparing reality-based survival fighting to the rules-laden combat sports such as MMA. In many cases, the ultimate intent of one is to kill while the other is to win. I have trained special military forces since Operation Desert Storm in 1992. Each time I work with them I consider their attire, the weaponry carried, and the fact that most of their skirmishes take place at close quarters. I also teach gross motor moves for rapid conflict termination.

What insights into the ideal fighting mindset have your experiences in street fighting, where your opponents could easily have drawn weapons and gone for the kill, given you?

JIM ARVANITIS: Just because a martial art is popular does not make it effective for serious self-defense. One must always be on the lookout for edged weapons, handguns, bludgeons, and mass assaults in a high-risk confrontation. This comes from my own experiences in street brawls where no rules or referees exist. A kill-or-be-killed mentality is paramount under these circumstances. Going to the ground is not an ideal ploy as there is always the risk of multiple assailants. Even if the fight does end up there, the goal should be to inflict heavy damage and return to your feet as quickly as possible. Getting a stable mount and looking for a joint lock, which works so well in MMA, is not really a wise choice here since locking the legs under an opponent’s thighs makes you vulnerable to others who decide to jump in to help their fallen friend. It’s better to stay upright where you can control distance and attack soft targets like the eyes, throat, and groin. Keep your kicks low and save your closed fist for body shots. Landing punches on a hard head can fracture your small bones and splay your wrist.

About the Author

Michael van Ginkel

Armed with a master’s degree in conflict archaeology and heritage, I’ve researched and excavated sites of conflict across the globe. I actively train and compete in grappling, the oldest combat sport in history

License & Copyright

The copyright holder has published this content under the following license: Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike. This license lets others remix, tweak, and build upon this content non-commercially, as long as they credit the author and license their new creations under the identical terms. When republishing on the web a hyperlink back to the original content source URL must be included. Please note that content linked from this page may have different licensing terms.