Published in: Van Ginkel, Michael. “Alexander’s Thracian Campaign – Into the Mountains.” The Ancient Warfare Magazine, Karwansaray Publishers, Vol. XII, No. 2, July 2017.

The Thracian campaign, initiated in the Spring of 335 BCE, reveals Alexander’s military skills and aptitude for command. While the subjugation of the tribes involved in the Balkan upraising remained Alexander’s foremost objective, the campaign contributed significantly to Alexander’s later achievements. A successful conclusion to the campaign allowed Alexander to leave for his Persian expedition knowing his kingdom and supply lines remained secure from rebellion. Alexander additionally increased the stamina and toughness of his inexperienced troops and field commanders through the unforgiving mountains of modern Greece, Bulgaria, and Romania. Lastly, Alexander developed tactics and strategies that would resurface in the more famous battles of his Persian campaigns, including Gaugamela, Issus, and minor engagements against hill-tribes.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Prepering to March

In the wake of Philip II’s assassination in the theater of Aegae in 336 BCE, Alexander ascended the throne. While he dealt with familial contenders for the kingship, the surrounding factions rebelled against the Macedonian hegemony. In retaliation, Alexander first marched south to bring Thessaly and Greece, through skillful military and political maneuvering, back into the Macedonian fold. While returning to the capital, Alexander learned of further troubles stirring in the Thracian tribes to the north. Ancient authors specifically attribute the uprising to the Triballi, a tribe from Northern Thrace singled out by Isocrates and Aristophanes for their uncivilized and belligerent nature. The term Triballi contains political, not simply ethno-geographical, connotations; fluctuations in tribal strength and territory size occurred regularly over the centuries along with shifts in alliances and loyalties.

Determined to preserve his father’s conquests in Thrace, Alexander spent the winter months preparing for a campaign to the north. Alexander’s forces consisted of mostly untried warriors. Before his assassination, Philip II had stationed the majority of Macedon’s most experienced soldiers, under the command of the respected commander Parmineo, in Asia Minor. Unwilling to further delay preparations for the Persian campaign, Alexander relied on newly-recruited soldiers for his expedition into the Balkans. The officers that accompanied Alexander into Thrace, such as Koinos, Perdikkas, Amyntas, Meleagros, and Philip, likewise formed a new cadre of commanders. The veteran leaders of the Macedonian army, including prominent figures such as Antipater, Antigonus, and Cleitus the Black, remained behind or joined Parmenio’s forces near the Bosporus straits. Having assembled his forces, Alexander began appraising the necessary logistics.

Although anecdotal in nature, Plutarch’s description of seven-year-old Alexander interrogating Persian envoys for topographical information draws upon a common Macedonian military practice. As Donald Engels has shown, before planning out his route, Alexander’s intelligence system of emissaries, local guides, deserters, and mounted skirmishers procured information on climate, geography, agricultural production, and enemy dispositions and numbers in Thrace. The Macedonians also used information collected by Philip and Parmenio during their past campaigns in the Balkans. Alexander’s choices in route subsequently reflected conscious and informed decision-making.

Battle of Mount Haemus

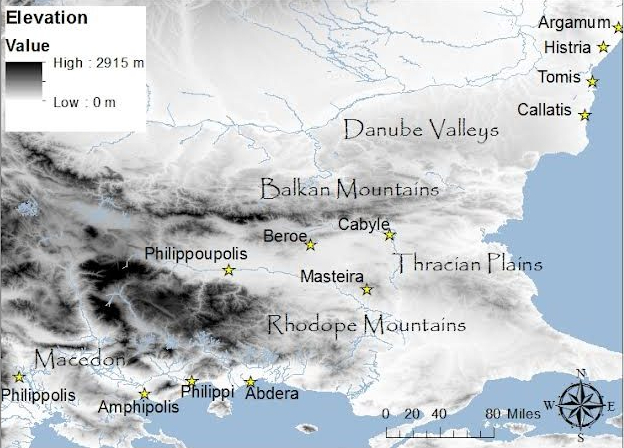

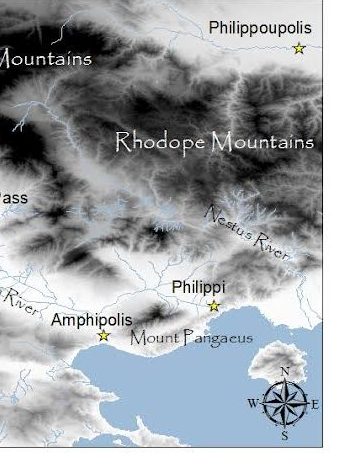

Alexander’s first task, after wintering in Amphipolis, lay in navigating the Rhodope Mountains to reach the central plains of Thrace. Firm control of the central plains held several strategic advantages. The fortifications and settlements founded by Philip, such as Philippopolis, Drongos, Kabyle, Masteira, and Beroe, provided military staging and resupplying points. Alexander’s march into Thrace ensured the continuation of the Macedonian hegemony installed by Philip during his campaigns in 353 and 342 BCE, which included fixed tribute, manpower, labor, and an acceptance of Macedonian foreign policy. Lastly, the fields cultivated by the local Thracian population also provided a substantial portion of the Athenian grain supply. By cementing the Macedonian presence, Alexander exerted pressure on the Athenian economy and provided leverage in political negotiations.

Aside from a few sentences worth of description by Plutarch, Diodorus, and Justinus, only Arrian dedicates a substantial section to the Balkan campaign. The temporal and topographical constraints imposed by Arrian’s account of the march aligns most closely with an inland route through the Rhodope mountains rather then around. Alexander’s earlier campaign against the Maedi tribe living along the valley of the central Strymon River in 336 BCE, his first independent command, would have insured personal, regional familiarity with this area.

The route of least resistance from Amphipolis, based on elevation, trails north between Mount Pangaeus and the town of Stathmos Lefkotheas before entering the Rhodope Mountains proper via the town of Panorma. The Nestus River is crossed toward the center of the mountain range between the towns of Teplen and Blatska. Finally, the trail reaches the Thracian valley near modern Pazardzik. Confirmation of the route’s viability in ancient times comes from evidence of a Roman Road following roughly the same trajectory. The route directly over the Rhodope Mountains provides precedence and early experimentation for Alexander’s future successes in marching armies across difficult terrain to catch enemies off-guard

After pacifying the Thracian plains, Alexander needed to cross the formidable Balkan mountain range to enter northern Thrace and Triballi territory. Although numerous passes cross the Balkan Mountain watershed, Alexander chose the Shipka pass; a major thoroughfare trailing from the town of Shipka in the Thracian valley to arrive in the Danube valley around the town of Garbovo. From a Macedonian perspective, the lower elevations and shorter marching duration for armies crossing Shipka pass, compared to other passes of similar magnitude, meant less opportunity for an ambush. The proximity of Shipka to the Macedonian garrisoned city of Beroe in the Thracian valley also created a natural launching point.

The Thracians reacted by sending a sizable force to the high ground offered by Mount Haemus overlooking the pass. The Triballi had neither the organization nor manpower to defend all feasible passes along the entirety of the permeable Balkan mountain range. Instead, the Triballi remained informed of Alexander’s movements and impeded his progress when the opportunity presented itself. The scenario mirrors Pompeius Trogus’ narration of the Triballi interception of Philip II’s army, where hearing that he was returning from his battle against the Scythians the Triballi had blocked his route through the Balkan Mountains and forced a confrontation. In a similar fashion, Alexander attempted to cross the Balkan watershed into Triballi territory and found his route barred by armed tribesmen forewarned of his movements.

Alexander’s first military encounter took place in the defile at the base of Mount Haemus, where the ‘Independent Thracians’ and local militia awaited his approach. As an additional defensive measure, the tribesmen had created a stockade of carts, which doubled as an offensive weapon when sent careening downhill towards the densely packed advancing Macedonian forces. Having observed the Thracian disposition and guessed at their intentions, Alexander immediately devised ways to counter the rolling carts. Depending on the availability of maneuvering space, Alexander ordered the Macedonians to react by either breaking formation and forming a corridor for the carts to pass through, crouching together and redirecting the incoming carts at an angle, or lying on the ground with interlocked shields and permitting the carts to pass overhead.

In the ensuing assault, the Macedonian troops executed the counter measures without suffering a single casualty. Notably, however, ancient accounts listing casualties usually fail to include statistics on men injured or proclaimed missing during an engagement. Having bypassed the first obstacle, Alexander quickly rearranged his battle-line before establishing contact with the enemy. Alexander had begun the attack by adopting a standard Macedonian battle formation, with heavy phalanx infantry in the center and lighter infantry protecting the flanks. Since the mountainous terrain rendered the Macedonian cavalry contingents unusable as mounted warriors, the cavalry left their horses with attendants and fought as infantrymen. Alexander placed these additional troops along his flanks to bolster his light infantry. During the initial advance, Alexander placed his archers on the right flank, using the extended front to ensure his units remained disentangled while avoiding the careening carts.

After they had successfully exploited the additional space afforded by the elongated formation, Alexander ordered his archers to redeploy in front of the phalanx, as it was easier to shoot at the Thracians wherever they attacked. Although the army had already surged forward in their eagerness to engage the opposition, the archers still managed to execute Alexander’s orders. Alexander himself took the Agema, Hypaspists, and Agrianians to deliver the finishing blow from the left while his center held the Thracian warriors in place. Despite the advantages offered by occupying rough terrain, which inevitably disrupted the cohesion of the Macedonian phalanx and thus created exploitable breaches in their formation, the inferior arms and armor of the tribesmen proved their downfall.

Having their own countercharge falter under a storm of arrows, the Thracians broke under the onslaught of the Macedonian central phalanx before Alexander’s charge connected.v15,000 of the tribesmen died while the remainder of the tribesmen, through their speed and intimate knowledge of the countryside, managed to escape in headlong flight from the mountain ridge. Alexander captured the women, children, and equipment within the enemy camp and appointed Lysanius and Philotas to guarantee their safe conveyance to the coastal cities for transportation. Arrian fails to mention the number of casualties inflicted on the Macedonians during the battle, but they likely suffered minimal losses given the brevity of the conflict and the decisiveness of its conclusion. From the beginning Alexander’s imaginative solutions to dangerous circumstances and his willingness to risk personal injury by leading from the front endeared him to his army.

Battle of Liginus River

After the battle of Mount Haemus the Macedonians completed their crossed of the mountain range unhindered before descending into the Danube plains. Alexander spent the next few weeks in Northern Thrace crushing the Triballi’s central strongholds. Discovering Cyrus, king of the Triballi, had withdrawn with the remnants of the Triballi resistance, along with neighboring Thracian tribesmen, to Peuce, Alexander set off in pursuit. Considerable primary, archaeological, and geographical evidence points to the Dunavat peninsula on the Danube Delta as the modern counterpoint for Peuce Island.

To reach king Syrmus, Alexander turned east to the Black Sea. As John Karavas points out, Reaching the Danube Delta by following the Black Sea coastline provided several strategic and logistical advantages. The coastal route allowed Alexander’s ships, summoned from Byzantium to rendezvous with the Macedonian army, to serve as mobile supply depots. Between the Balkan mountain range and Danube Delta, in the fertile area known as Dobrudja, the Greeks founded the major settlements of Callatis, Tomis, Argamum, and Histria, each an autonomous power excreting influence over nearby minor colonies and satellite communities. Similar to the Greek city-states along the Ionian coast, the colonies maintained a fluid relationship andhierarchy with the local tribes. Regardless of their enmity or friendliness with the native populations, ‘liberating’ these Greek colonies from Thracian hostilities suited Alexander’s pan- Hellenic image. The policy formed a precedent for Alexander’s later conduct along the Ionian Coast in Asia Minor during his Persian campaign.

Upon reaching the Danube, however, Alexander realized an enemy army had marched behind him. Fearing an outright battle, another Triballi force had concealed themselves along the Lyginus river and waited for the Macedonian army to march north. The maneuver neatly placed the Thracians force over Alexander’s lines of supply, communication, and retreat. The Macedonian intelligence system, however, again proved its usefulness by allowing Alexander to retake the initiative. Doubling back in a forced march, the Macedonians arrived at the Lyginus river before the Triballi could fortify their position in the nearby woods. The location of the Lyginus River, otherwise unmentioned in ancient literature, remains difficult to identify. Arrian’s description of a three days marching distance from the Danube Delta places the river somewhere in the Dobrudja valley.

Arriving at the Lyginus River, Alexander chose his deployment in the glen opposite the Triballi occupied tree-line carefully. Philotas commanded the cavalry of upper Macedonia on the right wing, while Heracleides and Sopolis lead the Cavalry from Bottiaea and Amphipolis on the left. The Triballi would find themselves hard-pressed to hold their lines when the Macedonian cavalry charge, deployed in their typical wedge formation, connected. The remainder of the cavalry, under Alexander’s direct command, held the ground in front of his infantry phalanx. Since Alexander placed the heavy cavalry from Bottiaean, Amphipolis, and Upper Macedonia on his flanks, the central mounted warriors likely consisted of light Prodromoi cavalry. As Nicholas Hammond explains, the projectile armed Prodromoi formed a mobile screen for the heavily infantry.

Once in position the phalanx adopted a formation midway between its normal and most compact configurations by maintaining individual frontage of three feet. Deviating from his customary battle arrangement Alexander also threw his phalanx into deep formation. Although the topographical variables potentially influenced Alexander’s choice of formation, the deeper phalanx undoubtedly held additional tactical and psychological benefits. The deeper phalanx ensured the Macedonian center would hold against any sudden charge erupting from the tree line. Alexander’s superiority in cavalry, in turn, forestalled any vulnerability to enveloping maneuvers created by the reduced battle line front. The formation also illustrates Alexander’s early experimentation in psychological warfare. As Stephan English hypotheses, Alexander intended to avoid having the light-armed Triballi retreat before giving battle out of fear. Instead, the reduced front on a level battlefield concealed the true extant of Macedonian numbers and worked to entice the Triballi into a headlong charge.

Alexander began the battle by ordering his light infantry considerably ahead of his main force, wanting to lure the Triballi from the narrow confines of the glen into the open. In Triballi complied, charging after of the archers and slingers to end the infuriating barrage of projectiles. During the uncoordinated pursuit of the Macedonian light infantry meant, the warriors of Triballi left pulled ahead of their comrades. Observing the opening, Alexander immediately ordered Philotas and his cavalry to smash into their disorganized ranks. Heracleides and Sopolis quickly mirrored the attack by engaging the Triballi right flank, while Alexander himself led the central components of his army in a frontal assault.

The synchronized, three-pronged attack broke the Triballi lines, forcing the tribesmen to flee back through the glen towards the Lyginus River. Encroaching darkness coupled with the dense foliage separating the glen from the river allowed the majority of Triballi to escape capture. The dead numbered 3,000 Triballi and some 51 Macedonians, including 11 cavalrymen. Alexander’s heavy reliance on mounted troops, both to envelope the enemy flanks and cover his infantry charge, further developed a new method of waging war pioneered by Philip II. The role played by cavalry at Lyginus River meant Alexander would continue to rely extensively on a mixed force composition in future battles.

Battle of Peuce Island

Victorious, the Macedonians again followed the coastline northwards and, three days later, reached the Triballi and Thracian refugees on Peuce Island. After linking up with the Macedonian fleet waiting at the Danube Delta, Alexander loaded a force of hoplites and archers onto the ships to assault the island amphibiously. But after vicious fighting, the Thracians managed to fend off the Macedonian attempt to establish a beachhead. More alarmingly, Alexander received new that another army belonging to the local Getae tribe, consisting of roughly 4,000 mounted men and over 10,000 infantrymen, had encamped out of line-of-sight on the opposite banks of the mighty Danube River. From their strong position, the Getae could resupply and reinforce the Thracian refugees on Peuce Island. Alexander subsequently decided to divert his attention to first neutralizing the threat posed by the Getae army.

Alexander again employed resourcefulness and daring in overcoming the natural defenses created by the Danube river’s considerable width. Taking inspiration from an ingenious ploy used by Xenophon to cross the Euphrates River, Alexander filled leather tent covers with hay to create makeshift flotation devices. In conjunction with local boats carved from felled tree-trunks, a design still used by local inhabitants today, Alexander managed to ferry 1,500 cavalry and 4,000 infantry across the river under the cover of darkness. Navigating across the 40-meter-wide Danube required a substantial amount of time and effort, but Alexander managed to complete the task without detection.

Landing behind a raised ground crowned with a wheat field, the Macedonians waited for morning. At first light Alexander advanced northward, infantry first, into the wheat field towards untilled ground. Alexander purposefully ordered his men to march with spears held parallel to the ground at an oblique angle to smooth down the wheat and allow the cavalry to easily follow in their wake. Alexander next took his cavalry, in wedge formation, to cover the right wing, leaving a Danube tributary branching northward to protect the exposed left flank of the Macedonian phalanx. Nicanor lead the center forward in a solid rectangular formation, adopting a greater depth then width in a manner similar to the deployment at Lyginus River.

Shocked at the sudden Macedonian appearance and the apparent effortlessness of Alexander river crossing, the Getae fled after only brief clash with the Macedonian cavalry Alexander’s decision to launch a cavalry charge, without first pinning the enemy formation in place with his phalanx, speaks to the disarray and confusion within the enemy’s ranks. Alexander followed in the wake of the Getae as they fled to a nearby city for refuge. Throughout the pursuit, Alexander guarded against a possibility of an ambuscade by leading with his cavalry and hugging the riverside with his phalanx. Noting the implacable and controlled nature of Macedonian advance, the Getae abandoned all hope of mounting a successful defense and abandoned the city. While the majority of women and children evacuated the area with their men folk, Alexander still captured a vast amount of plunder, which he entrusted to Meleager and Philip for transportation. Soon thereafter the remaining Triballi and the surroundings tribes offered submission.

Lessons Learned

The lessons Alexander, his new cadre of commanders, and the Macedonian army at large learned during the hard-fought Thracian campaign contributed directly to the later successes in Persia. Alexander would reuse the tactics employed against the rolling carts at Mount Haemus against Darius’ chariots at the battle of Gaugamela; the maneuvering of armies before the battle of Lyginus River at the prelude to the battle of Issus; and the use of leather tents filled with hay to cross the Ister at the crossing of the Oxus River. The precedent set in the Balkans provided Alexander with the experience and confidence to overcome seemingly insurmountable obstacles.

Heated debate surrounds Alexander military abilities based on victories in Persia and beyond. Alexander’s father introduced many of the innovative tactics and strategies that defined fourth century BCE warfare. By reorganizing and retraining the Macedonian army, Philip II left Alexander in command of an efficient military machine led by veteran battlefield commanders. The numerous advantages at Alexander’s disposal during his later campaign place into question Alexander’s own claim to greatness. During the Balkan campaign, however, Alexander fought without relying upon his considerable military assets. Moreover, the rugged Balkan terrain and fierce native populations created unique problems for Alexander’s unwieldy phalanx. Despite the difficulties, Alexander managed to defeat his opposition piecemeal and achieve his military objectives with minimal loss of life. In Thrace Alexander proved the veracity of his famed military reputation.

About the Author

Michael van Ginkel

Armed with a master’s degree in conflict archaeology and heritage, I’ve researched and excavated sites of conflict across the globe. I actively train and compete in grappling, the oldest combat sport in history

License & Copyright

The copyright holder has published this content under the following license: Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike. This license lets others remix, tweak, and build upon this content non-commercially, as long as they credit the author and license their new creations under the identical terms. When republishing on the web a hyperlink back to the original content source URL must be included. Please note that content linked from this page may have different licensing terms.